- Home

- Melissa de la Cruz

Frozen hod-1 Page 14

Frozen hod-1 Read online

Page 14

“It’s here!” hissed Zedric, just as a large boom resounded from the ceiling.

“Something’s hit the ship!” Farouk yelped.

“What now,” Wes muttered, releasing Nat and running toward the steps heading to the upper deck to see what had happened, but he was thrown backward as another boom echoed through the cabin, and now there was the sound of tearing—a ripping, horrible noise, loud and angry—as if the ship were being torn apart piece by piece.

“WHAT THE . . .”

The boat lurched as the first engine died, and started to spin in a broad arc, rolling hard to one side as the remaining engine drove them in an out-of-control circle. A moment later the second engine failed abruptly and the ship coasted to a stop.

“The engines!” Shakes cried as Wes leapt to run upstairs, but Farouk pulled him back. “Stop! We don’t know what’s out there!”

“Let me go!” Wes said, as he pushed Farouk away.

Nat followed him up the stairs.

“Stay back!” he yelled.

“No—if there’s something out there—I might be able to help!”

He shook his head but didn’t argue.

They ran up to the deck together and looked down. There was a massive steel engine hatch on the aft deck, tossed upside down like a tortoise shell. The other hatch was sinking quickly into the dark waters. Only bolt holes remained where the hatches had been torn from their mountings. In the bilge, the starboard engine was nothing but a smoking black void—a broken hose leaked gas and water into the pit. There was a hole in the bottom of the ship where the propeller had been torn free and water was pouring into the cavity. The port engine was still in place, but impossibly damaged. Its thick steel housing had fused together, melted, as if it had been run through a blast furnace. Shards from the motor were strewn all over the deck. One engine had been torn deliberately from the ship, and the other one completely burned.

“There!” Nat said, pointing out to the distance, where the darkness coalesced into a massive, horned shape above the water.

“Where?”

“I thought I saw something—” But when she looked again, a faint light shone through the clouds, and whatever it was vanished. She blinked her eyes—was it merely a trick of the light?

The rest of the crew crept up on board. Daran kicked at the remnants of the motor while Zedric muttered voodoo prayers under his breath. “The wailer did this . . . we’re cursed,” he whispered.

Shakes sighed. “So much for the trashbergs.” The massive trash mountains were the least of their concerns now.

“We’re stuck!” Farouk groaned. “Without an engine we’re dead in the water.”

“Looks like it.” Wes nodded, frowning.

Nat was silent as the crew contemplated the latest disaster.

They were adrift in a vast poisonous arctic sea.

28

NO ONE SLEPT. WHEN MORNING FINALLY came, Nat found the crew gathered on the deck. Wes had ordered them all back to bed the night before, the Slaine brothers grumbling and peeved, Farouk whimpering a little, at the latest setback with the loss of their engines. Only Shakes and Wes appeared untroubled.

“This is nothing.” Shakes smiled. “When we were in Texas, we went for a month without eating, right, boss?”

Wes shook his head. “Not now, Shakes.”

“Right.”

The boys were rigging a sail and Nat watched as Wes drove a bent crowbar underneath a plate in the center of the deck and heaved the square of steel upward. Zedric raised two more panels in the same manner.

“Secret compartments?” Nat smiled.

“It’s a runner’s boat,” Wes said with a grin.

Nat looked down through a crisscross of metal braces into the hold and saw a water-stained cloth wrapped around a steel mast.

A sail.

She was impressed. “You knew this was going to happen?” she asked.

“No, but I prepare for everything. You can’t sail the oceans without one.” Wes shrugged. “Never thought I’d need it, though. I never thought Alby would turn into a fifteenth-century ship. All right, pull it up, boys,” he ordered.

Shakes smiled. “See? I told you, we’ve got options.”

“Yeah, we’re not dead in the water just yet,” Farouk said. “C’mon, Nat, you know we got game.”

“Farouk, stop flirting with the lady and help me with this,” Wes grunted, and the boys struggled to erect the makeshift sail.

“Nice work,” Nat said, walking over to put a hand on his arm—an affectionate gesture that was not lost on him. Or the crew. She felt Wes stiffen under her touch, as if a jolt of lightning had sparked between them.

“Who’s flirting with the lady now?” Shakes laughed.

Nat blushed and Wes’s smile deepened.

There was a moment of solidarity and Nat felt that after the ugliness of what happened earlier, things had settled. The sail caught wind, and for now, everything would be all right.

* * *

That evening, Nat retired to her bunk in Wes’s cabin. Wes was already sleeping in the bed, an arm thrown over his eyes. He slept like a kid, she thought, looking at him fondly. The ship was moving silently through the ocean, the rocking had stopped for a moment, and Nat was glad. She turned her back to him, quickly changed into a T-shirt and climbed in next to him.

“Good night,” Wes whispered.

Nat smiled to herself. So he wasn’t as out of it as she had thought. She wondered whether he had watched her change, whether he had seen her out of her clothes, and she realized she didn’t mind—she was more than a little intrigued by the idea . . . all she had to do was turn around and put her arms around him . . . Instead, she fiddled with the stone around her neck, and the moonlight caught its glow, sending a rainbow of colors around the small cabin.

“What is that?” Wes asked, his voice low in the darkness.

Nat took a deep breath. “I think you know . . . it was Joe’s.”

“He gave it to you.”

“I asked for it,” she said. She could sense him stirring in the dark, next to her, and now he was sitting up, staring at the stone.

“Do you know what it is?” he asked.

Nat felt a reckless inhibition take hold, and the voice in her head was seething—telling her to keep silent—but she did not. “Yes,” she said finally. “It’s Anaximander’s Map.”

The smugglers and traders named it after the ancient Greek philosopher who charted the first seas. But on the streets they just called it the Map to the Blue. The pilgrims believed that the Blue was not only real, but that it had always existed as part of this world, merely hidden from sight and called different names throughout history—Atlantis and Avalon among them. They swore that the stories that had filtered down through the ages—dismissed as myth and fairy tale—were real.

She watched him absorb the news. She had always assumed he knew she had it, and that it was the real reason he had taken the job. Runners like Wes knew everything there was to know about everything in New Vegas. He might be a good guy, but he wasn’t stupid.

“You know the story, don’t you?” Wes asked. “How Joe won it in a card game.”

“I don’t, actually.”

“They said the guy he won it from was shot dead on the Strip the next day.”

Nat was silent.

“Why do you think he kept it for so long?” Wes asked.

“Without using it, you mean?”

“Yeah.”

“I don’t know.”

“Do you think it’s real?” he asked.

“He did live an awful long time; you know what they say, it’s supposed to be . . . well, keep you young or something. Anyway, look for yourself,” she told him, taking it off and handing it to him.

Wes took the stone and held it gently between his thumb and his forefinger. “What do you mean?”

“Hold it up, look through the circle. Do you see it?”

He did, and exhaled, and Nat knew he saw. “Joe

didn’t see it. He looked through it and saw nothing. Maybe the map wouldn’t reveal itself to him somehow. That’s why he never used it, because he didn’t know how.”

“This is incredible,” Wes said.

“How long till we get there?” she asked.

“I’m guessing ten days,” Wes said, studying the route. “More or less.” He told her that, as many runners had guessed, New Crete was the closest port, but many ships had crashed or beached or gotten lost in the dangerous waters of the Hellespont. This route sketched a hidden, winding passage through the uncharted waters, to an island in the middle of an archipelago. There were a hundred tiny islands in that grouping; no one knew which was the one that led to the Blue. Except for this map.

He gave it back to her to hold.

“Don’t you want it?” she asked, almost daring him.

“What would I do with it?” he asked her, his voice soft.

“Are you sure?” she asked.

For a long time, Wes did not answer. Nat thought maybe he had fallen asleep. Finally, she heard his voice. “I wanted it once,” he said. “But not anymore. Now I just want to get you where you need to go. But do me a favor, okay?”

“Anything,” she said, feeling that warm tingle all over again. He was so close to her, she could reach out and touch him if she wanted, and she wanted, so very badly . . .

“If Shakes ever asks you about it—tell him you got it a five-and-dime store.”

She joined him in laughter, but they both froze, as the sound of the wailer broke over the waves again—that awful, horrible scream—the sound of a broken grief—a keening—echoing over the water—filling the air with its mournful cries . . .

That thing, whatever it was, was still out there. They were not alone.

Part the Fourth

COMRADES AND CORSAIRS

Fifteen men on a dead man’s chest

Yo ho ho and a bottle of rum

Drink and the devil had done for the rest

Yo ho ho and a bottle of rum

-TRADITIONAL PIRATE SONG

29

WITH THE SAILS IN PLACE, THE TRIP moved in small, quick bursts, gaining speed and putting miles behind them, or none at all, as the ship moved at the mercy of the wind. Wes was on deck, in the crow’s nest at the top of the mast. He squinted. A small light emerged from the fog. It grew brighter and closer, and Wes could hear voices from the craft.

A ship!

Rescue!

Wes was not the type to believe in miracles but, against his better nature, he began to hope. If it was a mercenary ship, he might be able to make some sort of a trade—he just hoped it wasn’t a naval boat or a slaver. Then they were sunk. But if it was a fellow merc . . . Wes believed there was honor among thieves, among traders and vets and runners like him who worked on the fringes. Sure, they were scavengers and sellouts, losers and gamblers, but they had to work together, or they would be picked off one by one by the RSA, who would either throw them all in the pen or shoot them on sight, or by the slavers, who were far more dangerous and answered to no authority but their own.

He hadn’t told Shakes that Nat had told him about the stone, that she had confirmed it to be what they had suspected all along, and had even offered it to him. Why had he turned it down? He was supposed to take it—steal it from her—it was just a game to see who would win, who would give in first. Could he trick her into trusting him? He had won at last. So why did he feel as if he had lost?

She trusted him, so why was he so melancholy? Because Shakes would be disappointed, and didn’t he owe the guy his life? And more? Nah. It wasn’t that. Because if he’d accepted the stone and sold it to Bradley, they would be set up, rewarded, hailed as kings of New Vegas? Nah. It wasn’t that, either. Bradley could jump off a cliff as far as Wes was concerned, and as far as riches went, all he needed was a decent meal and a place to sleep and he was happy. He was in a bad mood because now they were closer to their destination than ever before. Only ten days away, and once they arrived there, he would never see her again.

That was what was bothering him.

There was nothing he could do to change that, nothing he could do to make her stay. He hadn’t planned on feeling this way, but there it was. Oh well, maybe he could make it up to Shakes somehow. Maybe today was their lucky day. There was a ship on the horizon.

“You see it?” he asked, climbing down to where Shakes was already at the rails with binoculars.

“Yeah. A boat.”

“What kind?”

“Hard to say.” Shakes handed over the binoculars and scratched the scruff on his chin. “Take a look.”

Wes did and his heart sank. It was a mercenary ship all right, but it was much worse off than theirs, without motor or sail. Just another unlucky crew like his, maybe even unluckier. The hull had a huge hole in it, but unlike their boat, it wasn’t patched, and the deck was quickly filling with dark water. It was sinking and was likely going to capsize at any moment. It was the ship’s luck to run into them, not the other way around.

He zeroed in on the crowd huddled on the deck. Through the green lenses, he could see a family with small children. They were waving frantically. Wes handed the binoculars back to Shakes, calculating the risks, the odds. Five more mouths to feed, he counted. Two of them children. They had so little already, they couldn’t possibly stretch their supplies any more; the soldiers were already eating bark. What could he offer this family?

His boys were massed on the deck, awaiting orders. The broken ship had drifted nearer, and now all of them could see who was on board and what was at stake. Wes knew how the Slaine brothers would vote, and Farouk would probably agree, although the adventure he had expected wasn’t turning out quite as he had hoped. They were all cold, hungry, and lost. But Shakes was ready with the rope, and Nat looked at him expectantly.

“We can’t just stand here and do nothing,” she said, almost daring him to argue with her.

“When you save someone’s life, you’re responsible for it.” Wes sighed. But even with his misgivings, he took the rope and threw it overboard, and someone on the other boat caught it. Better to let them drown, he thought; it was probably more merciful. But if he were that kind of guy, they would be heading to Bradley with Anaximander’s Map in hand and Nat in the brig.

With Shakes’s help, they pulled the sinking boat closer, and one by one the soldiers helped the family climb up on deck. The first to board was a young woman, draped in heavy black robes, her entire body and face covered in the black fabric so that only her eyes were visible.

“Thank you,” she croaked, taking Shakes’s outstretched hand. “We thought no one would ever find us out here.” Then she noticed his fatigues and shuddered. “Oh god . . .”

“Relax, we’re just a bunch of vets,” Shakes assured her.

Following behind her were a mother, father, and two children. The group of them huddled in a blanket. The parents were deathly ill, with pale and gaunt faces, profoundly malnourished, and Wes guessed they had been out here for several weeks with little water or food, and whatever there was to eat or drink had been given to the children.

“Where’s the captain?” he asked, taking the rope. The girl and the family must have been cargo; they looked like pilgrims searching for the Blue. This had to be a mercenary ship, but where was the crew?

He took the rope and climbed down to the sinking ship. Since he’d opted to do the right thing, he had to see it all through.

“Don’t—” the girl in black warned. “It’s—”

But it was too late, Wes was already on board and had headed down to the lower decks to see if he could find the crew. Down below, the empty cabins were filled waist high with water. He walked back up to the upper deck to the bridge, and there he found the answer to his question. Two deckhands, both dead—shot in the head, it looked like. The captain was at the helm, slumped over, cold and dead, another bullet in the middle of his forehead. The bridge was enclosed in glass on all sides. Wes could see

the holes where the shots had entered and exited. The bullets had come from another vessel, and the clean shots to the head told the rest of the story. If the ship had been attacked by slavers, the men would have seen them coming and hid from their fire. But the crew never saw these shots coming. Only a trained sniper could take out a mark from nearly a click. The dead men never even knew they were targets.

Whoever did this hadn’t even bothered to board the ship to look for passengers. With the crew dead and the hull leaking, the ocean would claim anyone left on the boat. Only the RSA would let its citizens drown and starve as punishment for crossing the forbidden ocean.

So, the naval carriers were out on patrol. They would have to be even more careful now, make sure none of the boys or Nat stayed up on deck during the daylight hours; the crew would hate it, no one liked being trapped down in the cabins, but if the snipers were out there . . .

The ship lurched to the side and Wes climbed quickly down the narrow stairs that led back to the deck. He nearly tripped on the last step. Something had changed, the walls were moving, the ship was taking on more water. The sinking ship had three open ports and maybe even a few blast holes that were allowing additional water to enter the craft, increasing her rate of descent as she sank quickly now into the sea. Wes reached the deck, but it was too late; one side of the craft had caught on the tip of a trashberg and the other was submerged below the water. The ship’s metal hull ripped and the ocean flooded in all around him.

Wes ran back to the bridge where the dead men rested. Their blank eyes stared at him from all sides. The black water was following him up the stairs. In a moment the ship would be entirely under water. He pulled the captain’s chair from its mount and rammed it through the broken glass. The shattered pane collapsed and the chair flew into the ocean. Wes climbed out, cutting himself as he struggled to reach the roof of the bridge.

He leapt from the wreckage toward the rope that was dangling from his ship, but the distance was too far, and he flailed, falling to the water.

Gates of Paradise

Gates of Paradise Someone to Love

Someone to Love Pride and Prejudice and Mistletoe

Pride and Prejudice and Mistletoe Serpent's Kiss

Serpent's Kiss The Au Pairs

The Au Pairs Wolf Pact

Wolf Pact Witches 101: A Witches of East End Primer

Witches 101: A Witches of East End Primer Jealous?

Jealous? Cat's Meow

Cat's Meow Misguided Angel

Misguided Angel Birthday Vicious

Birthday Vicious Return to the Isle of the Lost

Return to the Isle of the Lost Rise of the Isle of the Lost

Rise of the Isle of the Lost Angels on Sunset Boulevard

Angels on Sunset Boulevard Double Eclipse

Double Eclipse Blue Bloods

Blue Bloods The Ring and the Crown

The Ring and the Crown The Ashleys

The Ashleys Les vampires de Manhattan

Les vampires de Manhattan The Van Alen Legacy

The Van Alen Legacy Sun-Kissed

Sun-Kissed The Isle of the Lost

The Isle of the Lost Masquerade

Masquerade Witches of East End

Witches of East End Diary of the White Witch

Diary of the White Witch Crazy Hot

Crazy Hot Lost in Time

Lost in Time White Nights: A Vampires of Manhattan Novel

White Nights: A Vampires of Manhattan Novel Revelations

Revelations The Thirteenth Fairy

The Thirteenth Fairy The Birthday Girl

The Birthday Girl Lip Gloss Jungle

Lip Gloss Jungle Fresh Off the Boat

Fresh Off the Boat Something in Between

Something in Between Winds of Salem

Winds of Salem The Queen's Assassin

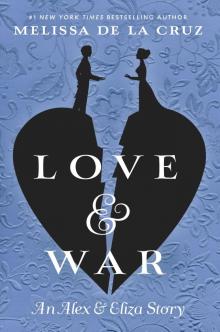

The Queen's Assassin Love & War

Love & War Social Order

Social Order Skinny Dipping

Skinny Dipping 29 Dates

29 Dates Popularity Takeover

Popularity Takeover Escape from the Isle of the Lost

Escape from the Isle of the Lost Beach Lane

Beach Lane Bloody Valentine

Bloody Valentine All for One

All for One Wolf Pact: A Wolf Pact Novel

Wolf Pact: A Wolf Pact Novel The au pairs skinny-dipping

The au pairs skinny-dipping Lip Gloss Jungle (Ashleys)

Lip Gloss Jungle (Ashleys) Crazy Hot (Au Pairs)

Crazy Hot (Au Pairs) Because I Was a Girl

Because I Was a Girl Blue Bloods 6 - Lost in Time

Blue Bloods 6 - Lost in Time Sun-kissed (Au Pairs, The)

Sun-kissed (Au Pairs, The) Bloody Valentine bb-6

Bloody Valentine bb-6 Golden

Golden Lost in Time_A Blue Bloods Novella

Lost in Time_A Blue Bloods Novella Alex and Eliza--A Love Story

Alex and Eliza--A Love Story Blue Bloods: Keys to the Repository

Blue Bloods: Keys to the Repository Birthday Vicious (The Ashleys, Book 3)

Birthday Vicious (The Ashleys, Book 3) Keys to the Repository

Keys to the Repository Lost In Time (Blue Bloods Novel)

Lost In Time (Blue Bloods Novel) Stolen

Stolen Girls Who Like Boys Who Like Boys

Girls Who Like Boys Who Like Boys the au pairs crazy hot

the au pairs crazy hot Blue Bloods bb-1

Blue Bloods bb-1 Witches 101

Witches 101 How to Become Famous in Two Weeks or Less

How to Become Famous in Two Weeks or Less Frozen hod-1

Frozen hod-1 Jealous? (The Ashleys, Book 2)

Jealous? (The Ashleys, Book 2) Misguided Angel (Blue Bloods)

Misguided Angel (Blue Bloods) Winds of Salem: A Witches of East End Novel

Winds of Salem: A Witches of East End Novel The Gates of Paradise

The Gates of Paradise Beach Lane Collection

Beach Lane Collection Wolf Pact, The Complete Saga

Wolf Pact, The Complete Saga Gates of Paradise, The (Blue Bloods Novel)

Gates of Paradise, The (Blue Bloods Novel) Vampires of Manhattan

Vampires of Manhattan Isle of the Lost

Isle of the Lost Love & War_An Alex & Eliza Story

Love & War_An Alex & Eliza Story The Ashley Project

The Ashley Project Love & War--An Alex & Eliza Story

Love & War--An Alex & Eliza Story